My Story: A Childhood Between Two Worlds

My name is Orlando Ramírez. I'm a psychologist, entrepreneur, and the founder of Pneuma. But before all that, I was a 14-month-old baby given by my biological mother to two American missionaries because she, deprived of freedom, had no way to care for me.

Jerry and Shirley Margraves received me into their home in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and raised me alongside four other siblings in similar situations. I grew up in a bilingual environment, safe, with material and spiritual abundance. While at home I breathed American culture, outside I developed my Bolivian roots. I dreamed of being like Jerry and Shirley: people who loved God and served the most vulnerable.

For over 18 years, the Margraves directed a ministry in Cochabamba's prisons, bringing dozens of children who lived behind bars with their mothers to a space where they could simply be children. Monday through Friday, these little ones received breakfast, education, recreation, lunch, and snacks before returning to the prison facilities at day's end. It was through that ministry that Giovanni, Marilú, myself, and later Armando and Scarlet came to our family.

When Jerry's health problems worsened—he had suffered a stroke in 2001 that paralyzed half his body—and the couple had to return to the United States in 2011, only Scarlet could accompany them. She was the only one with legal adoption. The rest of us, already adults, stayed in Bolivia. I was 19 years old.

The Transition to Independent Life

At 19, when the Margraves left, I faced the reality that thousands of young people graduating from orphanages face in Bolivia: independent life without a family network. I started studying civil engineering motivated by economic stability, but after three years I discovered my true interest was in helping people. I switched to psychology at the state university.

I rented small rooms, worked while studying, and learned to manage limited resources. There were difficult days—simple meals, long walks to save bus fare, tight budgets. But I had something many orphans don't have: developed social skills, bilingual education, a solid spiritual foundation, and the ability to adapt to different cultural contexts.

Those tools were my advantage. I knew how to communicate with confidence. I knew how to look for opportunities. I had emotional resilience built in a stable home during my first 19 years. It wasn't easy, but it wasn't impossible either.

I became actively involved in church as a worship leader, Sunday school teacher, and summer camp counselor. I went through a personal crisis where I questioned my path and priorities, but that stage taught me something crucial: no one was going to rescue me. I had to build my own future.

That mindset led me to finish my psychology degree, get my first professional job at an orphanage, and eventually build my own private practice. In 2023, seven years after their departure, I was able to travel to the United States to reunite with my mom Shirley and my sister Scarlet—an achievement that symbolized how much I had grown since that 19-year-old young man who stayed in Bolivia.

Armando and the Cost of a Failed System

Among the five children who grew up with the Margraves was Armando. He came to the family when he was only weeks old, after his biological mother completely rejected him. Unlike those of us who had years of stability before facing independence, Armando never knew that security.

When the Margraves left in 2011, Armando was only 10 years old and lacked the necessary documents for legal adoption. A Bolivian family from church offered to adopt him, but when the time came, they backed out. By then, options had run out. He was admitted to a care facility.

Years of abandonment and early trauma had left deep scars. He was later diagnosed with schizophrenia, a condition that caused hallucinations and delusions. In his desperate search for affection and belonging, he escaped from the first facility. He was placed in a second, then a third. At 16, Armando was living on the streets of Cochabamba, sleeping inside ATM booths.

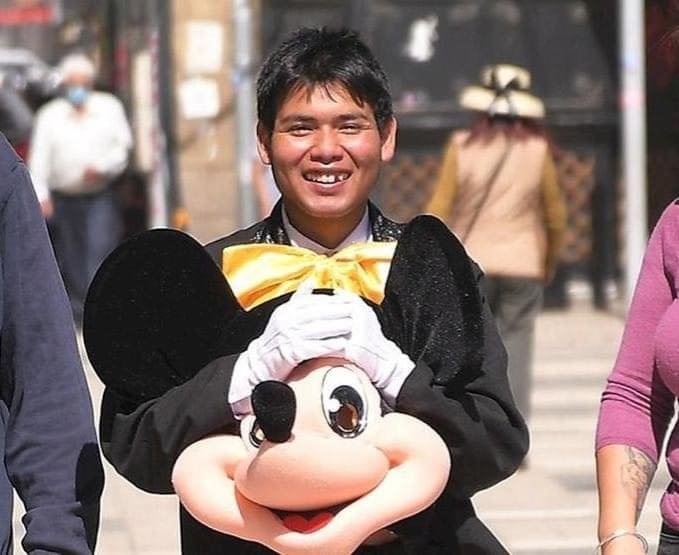

Despite everything, Armando had a remarkable artistic spirit. He loved dance, music, and cartoons. He earned money working in a Mickey Mouse costume in the main plazas, posing for photos with children and families. His sociable and affectionate nature made him a known figure in the city. Many people, families, and churches tried to help him, but the street had become the only place where he felt he belonged. Even the mayor of Cochabamba offered him a job that seemed more a political gesture than a real solution.

In December 2021, I rented a larger house and took Armando in. Living together was complex. His mental instability complicated the daily routine, and his confused accounts occasionally created misunderstandings. He suffered frequent fainting spells and serious health problems. Eventually it was discovered that he had an illness that had destroyed his immune system as a consequence of years of abuse on the streets.

In October 2022, Armando contracted tuberculosis. His body no longer had defenses. He passed away at 22 years old.

His story left a painful but clear lesson: love, no matter how genuine, is not enough if it doesn't come with structure, practical skills, and a clear purpose. Young people like Armando don't just need a roof and food. They need tools to build autonomy. They need to learn at 12, 14, 16 years old what many orphanage graduates never learn: how to manage money, how to maintain a job, how to make healthy decisions, how to build stable relationships.

Mente - Psychology Practice: Learning to Build

In 2019, while working at the orphanage, I started my own psychology practice called Mente - Psychology Practice. At first it was just me in a small office. What I learned in my years of transition to independent life was this: I had to create my own path.

I applied that mindset to my practice. I studied digital marketing, administration, personnel management. Mente grew to the point where I had to hire other psychologists and form my own firm. I learned to delegate, establish systems, think like an entrepreneur and not like an employee.

That knowledge didn't come from a book. It came from direct experience.

Years later, when I started Pneuma, I realized that trajectory had prepared me for something bigger: I wouldn't teach academic theory about entrepreneurship, but proven strategies that had worked in the Bolivian context. Today I dedicate 60% of my time to Pneuma, 20% to Mente (delegating much of the operations), and the remaining 20% to my personal life. Mente finances my livelihood, which allows me to lead Pneuma without depending on donations for my personal survival. This gives me credibility with the young people: I speak from experience, not from a desk.

Why Pneuma Exists

In Bolivia, the system is designed around family. When you turn 18 and leave an orphanage, you don't have access to student scholarships, government loans, or housing programs like in other countries. Your family is your survival network: it gives you shelter, food, contacts, opportunities.

Orphans don't have that network. They leave at 18 with empty hands.

I worked in an orphanage. I saw teenagers with little cognitive stimulation, without social skills, without resilience. After years of following institutional orders, they didn't know how to make their own decisions. The Bolivian job market is rigid: if you don't arrive on time, you're fired. If you don't know how to manage money, you go from job to job. If you don't have an entrepreneurial mindset, you end up trapped in unstable jobs that barely cover your needs.

Pneuma was born from my personal experience, from Armando's death, and from the conviction that these young people need more than charity; they need training for autonomy.